David Chapman: From Amateur to Professional

In our interview series “From Amateur to Professional,” we will be asking established nature photographers to share how their photos and practices have developed, changed, and improved over time. You’ll get to see the progression of their images, learn how they got started, and find out how they transitioned from amateur to professional. To see more from this series, subscribe to our free newsletter.

Originally a maths teacher, David Chapman has been a professional photographer and writer for the last 20 years, specialising in wildlife and landscape photography. He has undertaken many photographic commissions, lectured on the Marine and Natural History Photography degree course at Falmouth University, and written 13 books about wildlife and photography in his adopted county of Cornwall where he has lived for the last 25 years.

When and why did you first catch the nature photography bug?

My father was a keen amateur photographer; he encouraged me to show an interest in photography and taught me how to process and print my own black and white films. I was given a 35mm compact camera as a present when I was about 12 years old and then saved up enough money to buy myself an SLR camera when I was 16. It was a Praktica MTL3 and cost £50 in 1981. Funnily enough, I have just checked it out on eBay and found one for sale at £62 – so now I wish I’d kept it as an investment!

In parallel to my photography, from a very young age I was taken out into the countryside to go camping every weekend. Despite my parents having only a passing interest in wildlife, I used my time in the country to begin learning about natural history – with birds being a particular interest.

When I was 17 years old, I bought a 500mm mirror lens, using money I had saved from a part-time job in a bingo hall in Blackpool, and began pointing that enthusiastically at birds in my local nature reserve. I had limited success but was happy being out photographing wildlife.

Between the ages of 18 and about 25, I concentrated my efforts on getting a degree and teaching maths. I maintained an interest in both photography and nature, but didn’t think I would ever be able to leave teaching to follow my hobby as a career.

Show us one of the first images you ever took. What did you think of it at the time compared to now?

The first images I took are not in existence any more. I am quite ruthless in getting rid of unnecessary clutter. I can share my first ever published photo, which was of a ring-billed gull. This image was published in the rarity section of Birdwatch magazine in 1993 and reflects my interest, at that time, for rare birds in the UK.

I can’t claim that this is a great photo, it is fairly sharp and the light is good but there is no action. At the time I was happy to get a frame-filling photo of a rare bird, though being honest it was a very obliging individual. I was even happier to get it published, but I never kidded myself that there was serious money to be made out of having rare bird photos published.

Nowadays, I tend to shun the idea of photographing rare birds because I don’t like twitching and there is a certain amount of the antagonism and prejudice shown by some birdwatchers to photographers.

Show us two of your favourite photos – one from your amateur days, and one from your professional career. Tell us why they are your favourites and what made you so proud of them at the time. How do you feel about the older image now more time has passed?

When I was transitioning from teacher to wildlife photographer, I undertook a project to photograph a buzzard using a wide-angle lens. I put out a dead rabbit every day for a few weeks to attract a buzzard to feed. Then I put out a black wooden block next to it every day for a week or so to simulate a camera being present. Once the buzzard had become accustomed to it, I started putting my camera out and running a remote release wire from our field to the bottom of our garden. Every hour or so I would stop working and go to the bottom of the garden to see if a buzzard was present, and if it was I would take a photo.

Everything that could go wrong did go wrong, and in the days of transparency film it would take a week or more to see what I was or wasn’t getting on film! After about three months of failing, I bought a CCTV camera which I wired up to my television in the house so I could see exactly what was happening and then I could l press the shutter release at the right moments.

On reflection, I was pleased with the photos but they did take a lot of time so they have never proved to be worthwhile financially. I enjoyed the process of problem solving and still enjoy that aspect of nature photography. When I give talks, people enjoy listening to my stories about how I take some of my photos.

As a more recent image, I am including a photo of a swallow which had just taken a drink whilst in flight. I think it is a good photo and it is certainly a difficult photograph to take. I am proud of it because it was on our own land in a pond we created for wildlife, and because I used my own initiative and skills to get the photo.

I prefer to create the photo from start to finish, in this way. In an increasingly commercial world there are many opportunities for us wildlife photographers to take images which have been set up by other people. I have nothing against this, and have done it a few times myself, but it is more rewarding to have a vision for a photo and seeing it through to a conclusion independently.

When did you decide you wanted to become a professional photographer? How did you transition into this and how long did it take?

I always wanted to be a nature photographer but I never dreamt that I would be able to turn it into a profession. The point at which my life changed was when I married Sarah and we bought a smallholding in Cornwall in 1995. We were both teaching at the time so had a steady income and I started to invest my spare time and money into photographing wildlife on our land.

Read more: Breaking Into Business

I began to have occasional photos published and also started to write articles. I got to a point where I thought I might be able to make a sensible amount of money if I could stop teaching. The defining moment that lives with me was when my headmaster took me in for a career interview and he asked me “where do you see yourself in three years’ time?”

Since I was the head of a large department at the time, I’m sure he was expecting me to say I wanted to become a deputy head or something similar. But I decided to be honest and told him I wanted to be a wildlife photographer.

That brought the career interview to an abrupt end because he didn’t know what to say. Anyway, 2 years later I asked him if I could go part-time. He agreed, and 2 years after that I left teaching and since then (2003) I have been a full-time professional photographer and writer.

Was there a major turning point in your photography career – a eureka moment of sorts?

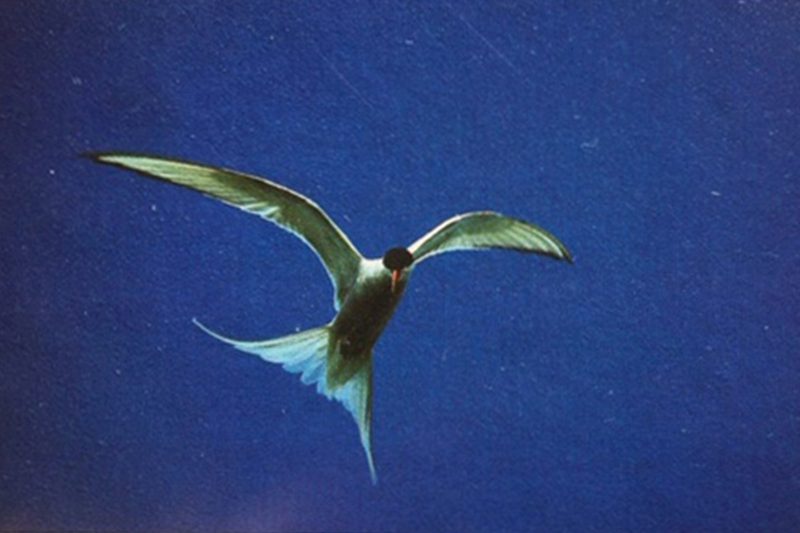

In 1995, I had a photograph of an Arctic tern in flight commended in the RPS Nature Group exhibition. This exhibition came to my local town: Helston, in Cornwall. I went to it and met a couple who belonged to Cornwall Wildlife Trust (CWT) Photographic Group. I went with them to this group and while I was there met people from a camera club which I also joined. Within a few months I was chairman of one and treasurer of the other.

I have been quite heavily involved with CWT since then, being a trustee for nine years and I have been chairman or secretary of their Photo Group for more than twenty years. Through my involvement with CWT I have learnt a great deal about wildlife and conservation, particularly in my adopted county of Cornwall, and through membership of camera clubs I continue to learn about photography.

Are there any species, places, or subjects that you have revisited over time? Could you compare images from your first and last shoot of this? Explain what’s changed in your approach and technique.

I revisit every subject and never get bored spending time with wildlife. Generally, each time I return to a subject I am aware of what I achieved last time and next time I try out a different technique, so I suppose my photography has evolved gradually to become more adventurous.

When I started out as a professional I worked in transparency film, so each shot had an associated cost (probably about 30 pence per image). This limited my willingness to experiment, though. So in the early days I would be happy to get close enough to get a photograph of a dragonfly. Over the years I have become far more discerning, trying to get more pleasing images and even capturing them in flight.

Even with static portrait shots of wildlife, the better technology available today has enabled us to take better photos. My early images of badgers were all taken with flashguns using transparency film. I started with one flashgun and, over the years, advanced to using three – generally two from the front and one from the back – and while this is still an option today, I much prefer to increase the ISO and avoid the need for flash altogether. Even when used well, flash does increase the contrast and with a black and white animal you don’t really need any more contrast!

Read more: Does Flash Photography Harm Animals?

What’s the one piece of advice that you would give yourself if you could go back in time?

Buy the best equipment you can afford, even if that means having fewer lenses and not so many other gadgets. Don’t try to buy lenses that ‘do everything’ because they always compromise on quality. Looking back though my own career, I have taken too many photos that are not good enough because they were taken with inferior lenses or filters because I was reluctant to spend a lot of money on what was initially a hobby. I started to put that right in 1995 when I bought my first professional lens: a 600mm f/5.6 Pentax which was razor-sharp, and I never looked back.

If I could extend this question to offering advice for others just setting out in photography, I would say that one thing I have gotten right throughout my career is to diversify my portfolio. That’s a pretentious way of saying that I have always looked for new ways to make a bit of money. So, over the years I have: written for magazines; I have now written 14 books; produced photo products such as fridge magnets; I give talks to photography and other groups; I have lectured in photography at university; I lead workshops (one-to-one and groups); I take guided nature walks; I provide framed photos for sale and to furbish hotels and other public spaces; I sell images through photo agencies; produce a number of calendars and I have undertaken a number of photography commissions from choughs to the gardens of Cornwall.

But I am very pleased to say that I have never photographed a wedding – that must be stressful!

Has anything changed in regards to how you process and edit your images?

This question was obviously written by someone much younger than myself! The answer is clearly yes because when I set out there wasn’t any such thing as ‘editing your photographs’. You got it right in camera or you threw the transparency in the dustbin, so most weeks I had a dustbin full of transparencies!

Generally, I don’t do much editing to my natural history images, although I have started to do a little focus-stacking sometimes with macro work. Editing of wildlife images is limited to light and contrast work, as well as cloning out dust-spots.

The editing question is more pertinent to my landscape photography. In the early days I never really saw myself as a landscape photographer, but about fifteen years ago I realised that I needed to improve this aspect of my photography because I wanted to have shots of habitats for my nature articles and I also found that photographs of landscapes sell better than wildlife in many arenas.

I set about teaching myself how to compose landscape images and began to appreciate when and where to go at various times of year and day. In short, I developed a better understanding of light in the landscape.

At the same time I started to develop more skills in the editing of these images, but in the early days it was time-consuming and not always successful. I made some awful hashes along the way.

My skills in editing are better now; I actually spend less time doing it and I get consistently better results but I don’t use anything fancy. I shoot in raw and use Adobe Camera Raw for 95% of the processing that I do. There are many occasions when I look in my files for a photo of a particular scene and find that I have a good photograph but that my previous editing was dreadful so I begin again from the raw file. Thank goodness I didn’t bin any raw files.

What was the best mistake you ever made?

The funniest mistake I ever made was when I was writing an article to accompany my photographs. I had spent a morning in a hide with a friend of mine, Adrian Langdon, who is warden of Walmsley Sanctuary (a nature reserve in Cornwall). The idea was that I would interview him whilst in the hide about the management of the reserve and we would take some photos to accompany the article that very day.

The hide was placed in the middle of the marsh without any footpaths leading to it and we had to be in the hide under cover of darkness. When I returned home I wrote about the experience and described how difficult it was to get out to the hide by saying: “the ground underfoot gave way to varying depths, occasionally threatening the tops of our wellies.”

I saved the article and sent it to Adrian for proof-reading and within a few minutes he was on the phone to me laughing uncontrollably. What I had actually sent to him read like this: “the ground underfoot gave way to varying depths, occasionally threatening the tops of our willies.”

Spell-check has a lot to answer for!

You can visit Chapman’s website to see more of his work. For more from this series, subscribe to our free Nature TTL newsletter.