Star Trail Photography: How to Shoot Moving Stars

Night time photography is often thought of as quite a daunting task, but it’s not as difficult as you may think, especially when it comes to star trail photography. Photography is all about experimentation for me, and there’s nothing better than capturing the mesmerizing beauty of the night sky by creating captivating star trails.

Now, what exactly are star trails? In simple terms, they are the result of long exposures of the night sky. The objective is to capture the enchanting movement of the stars as the Earth rotates.

Incorporating star trails into your photographs can infuse everyday scenes, whether they feature derelict buildings, monuments, or even your own backyard, with a sense of wonder and dynamic energy.

By adding an interesting foreground element, you can truly create a winning composition that captivates viewers.

Shooting Methods for Star Trail Photography

When shooting at night your aim is to maximise the amount of light coming into your camera. It may sound obvious, but one problem is that at night it’s usually fairly dark and light is limited, so you’ll need to allow for this and tweak your camera settings to accommodate. There are two approaches to star trail photography.

With both techniques, it’s always important to implement correct long exposure techniques, such as having the mirror locked up / being in Live View. You should also use a remote release to counteract any camera shake induced by touching the camera, as well as a sturdy tripod.

1. Using the Bulb Mode

The first method is to take a single long exposure. This is done by switching the camera to the Bulb (B) mode. This means that the shutter is open for however long the button is pressed, and light is exposed on the sensor. You’ll need to connect a cable release to your camera to do this correctly as you don’t want to shake the camera whilst pressing the shutter – and holding your finger on the shutter for over an hour is less than convenient!

But there are many downsides to this method. Firstly, you are putting all of your eggs in one basket. Imagine that you’re 30 minutes into an hour sequence and you knock the camera or kick the tripod leg (easily done in the dark); now the whole sequence is ruined. While the sensor is exposed to light, it will record the movement of anything in the scene. So, in this instance, if you continued shooting afterwards you’d have nice trails up to the point when you nudged it, and then the trails would be out of line.

Another downside is that you can only shoot when the moon isn’t out. If you did, over the course of an hour you’d be letting in a lot of light, so the scene will be overexposed by the moonlight.

Lastly, you get will get a build-up of heat on the sensor. This is where you get coloured dots scattered across your frame. Also, I personally think it’s best practice not to allow your sensor to expose for such a long time at once as it will shorten its lifespan.

2. Taking Multiple Consecutive Frames

The other method for photographing star trails is to take multiple consecutive frames and overlay them on top of each other during post production. The process afterwards is called stacking and is carried out by specific software (some recommendations later on in this article).

By shooting sequential frames on your camera not only do you keep overall failure to a minimum, but it’s also easier on your sensor as it allows it to cool between frames. The beauty of shooting lots of frames is that if there are distracting objects in your images (such as plane trails or car lights) you can always overcome these at the end of the sequence by cloning them out before the final compilation.

Also, if you do nudge your camera slightly you can discard that one affected frame and the rest of the sequence isn’t ruined.

Another plus point for me is that you can then turn your sequence of star trail shots into a time-lapse film. It’s always great to get two products out of one shoot!

Your exposure times should be just enough to expose the stars and any foreground you want in the shot, and as you’ll be compiling all of your images together you shouldn’t move your tripod. You can then shoot your foreground subjects differently, or even light paint them, and use that single frame in the final compilation.

The only downside to shooting star trails this way is that you’ll end up with a lot of image files and this will take up a lot of memory.

Essential Gear for Star Trail Photography

The bare minimum of equipment for a star trail sequence is a camera with a manual mode, so that you can set the shutter speed, aperture and ISO values manually. Bring fully charged batteries as the cold night air will sap life from them. A shutter release cable with a lockable shutter button is another key piece of kit. This, together with putting your camera onto continuous drive mode, will allow you to continuously activate the shutter one frame after another without touching it.

You must also have a sturdy tripod. Double check everything is tightened up before starting your sequence and make sure it won’t topple or slip. Other recommended items would be a warm clothing, a chair, torches, and warm drinks for those cold nights. Remember you’re going to be out in the cold for a good few hours, so keeping warm is important, otherwise it can become a miserable experience. Just remember not to nudge the camera or cast any stray light from your torch and phone across the scene or camera!

The Right Settings for Star Trails

Personally, I would say the multiple frames technique is the one to go for. With that in mind, stick your camera into manual mode. The first thing to think about is focusing and your aperture. What kind of depth of field do you need for shooting the stars? Shouldn’t you use a narrow f stop, such as f/8, as surely that would make things sharper? Well, the issue with photographing the stars is that they move… well, the Earth moves, but on our camera screens it’s the stars that appear to move. We don’t need to freeze the motion (as the trails are our aim anyway) but we do want to find a balance between the exposure for the sky and the exposure for any foreground.

For star trails I shoot wide open (f/4 for instance) which will let loads of light in, plus it will keep your ISO values lower than if shooting the same scene at f/8. Wider apertures will allow for shorter exposure times, meaning lots of final frames to compile together.

I always aim to shoot at the longest preset shutter speed of 30 seconds, at the widest aperture my lens will go to. I then adjust the ISO to result in a well exposed scene. Remember to do some test shots yourself and to change the aperture around to see what’s best for your location.

Now for your focus. As you’re taking a star trail and not a wide night sky image, it’s not 100% critical to focus on the stars, however I always do as best practice. If you can autofocus on them then great, if not then manual focus is needed. I always look for a bright light source near me when I’m out, be it a distant light, radio mast, or something that’s a fair distance away. Turning Live View on and magnifying the screen over the light source will help you to pinpoint it. Then, it’s just a case of manually focusing on it using the focusing ring on the lens. Remember to set your lens to manual focus so the camera doesn’t adjust this in between frames!

Note that you won’t always find yourself focusing to the infinity symbol on your lens (should it have it) as these don’t always show the true location of infinity focus. A great tip for star photography is to buy a lens like the Samyang 14mm f/2.8, and focus it to infinity during the daytime and tape up the manual focus ring to secure it in place.

If you want a sharp foreground too then you can photograph it as a separate frame after the main star sequence, focusing on the foreground and then overlay the foreground using masks and layers in Adobe Photoshop. Or, if you shoot with a wide enough lens and there’s a decent distance between the camera and foreground, then the foreground may be sufficiently in focus. The best thing is to experiment and learn what works for you and your camera.

Choosing a Direction to Shoot In

You’ll notice that not all star trails look the same. This is down to the direction the camera is pointing in relation to sky. If you want circular star trails in your image, then point your camera towards the north or south poles. If you’d rather have straighter star trails, then point your camera towards the east or west.

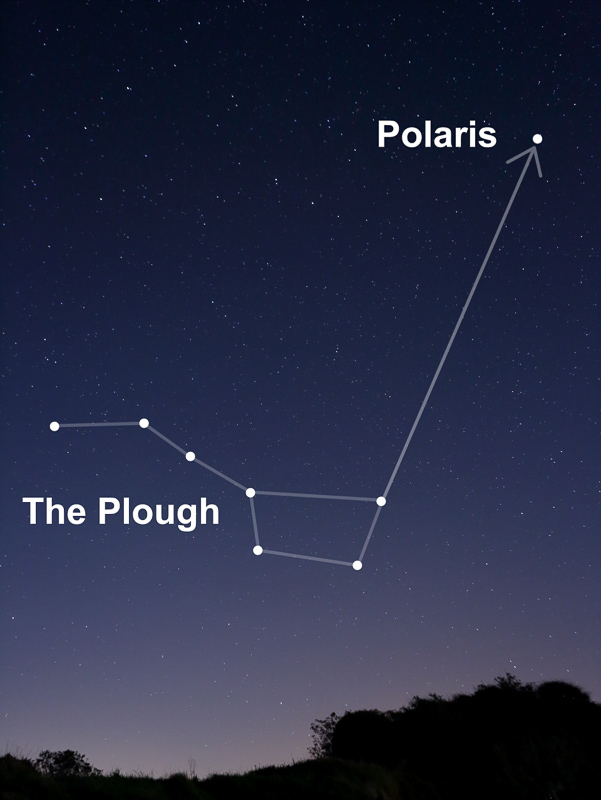

If it’s your first attempt, then try a circle around Polaris (the North Star). To easily find Polaris, you must first find the constellation of The Plough (in Ursa Major) and follow the vertical stars that make up the edge of the pan-shape upwards. Everything in the night sky will appear to revolve around this star as it’s the closest one to the Earth’s axis.

When choosing locations you should also think about anything that may affect the sky during a long exposure, such as light pollution or clouds. It might not look like much to the naked eye, but shooting a long exposure towards a town or city will make your skies go orange. Sometimes this can be used to produce a nice affect, but it is always another thing to think about. Also, I prefer shooting when there’s a full moon. Not only does it really give the night sky a punch of blue colour, but it will help bring life to your scenes by illuminating your foregrounds. If you shoot extended sequences in these conditions, you’ll get some great moving shadows in any time-lapses you create.

Further Reading: Choosing the Best Foreground and Background

Check List

- Make sure your tripod is stable and tightened up.

- Check your composition and your focus to ensure the stars are sharp.

- Set your lens to manual focus so the camera doesn’t change the focus between frames.

- Set your camera to continuous shooting mode (burst mode).

- Use a shutter speed of 30 seconds; aperture wide open; ISO to balance the exposure.

- Ensure the cable release is plugged in.

- Depress the cable release button and lock it down.

- Wait at least an hour for maximum effect.

Processing Photos of Star Trails

Hopefully all went well and you’ve got a memory card full of lovely images. Download these and import them into your processing software, such as Adobe Lightroom. Make sure whatever you do to one image, you do to all the frames in the sequence. You can do this by syncing your settings across the sequence. I usually do white balance, lens profile and other minor tweaks at this stage. Export these out as JPEG or TIFF files.

Processing Help: All You Need to Know to Process a Raw File in Lightroom

The best star stacking software I’ve grown to enjoy over time is StarStax, a free program downloaded from this website. It’s available for both PC & Mac and is a quick and easy way of creating your trail compilations.

Once you have downloaded and installed the software, open StarStax and press the ‘Open Files’ button. Navigating to your folder, choose all of your processed frames of the sequence. Once they’ve loaded into the program, it’s just a case of pressing the ‘Start Processing’ button and watching your star trail image unfold before your very eyes! Finally, save the resulting image at as high a quality as possible (TIFF) and you’re done! Often I will re-import the outputted image into Lightroom for some final adjustments.

As you may notice, there’s lots more to play with in StarStax, such as changing the Blending Mode options. These will give you different ‘looks’ to your final star trails compilation. It’s worth testing a few out to see which one you like most! Have a dabble with the Comet mode, as that will slowly intensify your trail lines to appear like circular comets.