How to Take Outdoor Photographs for Paying Clients

As is the case with so many photographers, especially those that read articles on Nature TTL, I have always loved working with outdoor subjects. Whether this is macro, long lens, or landscape photography, much of my spare time over the years has been dedicated to building these skills.

However, understanding how to turn photography skills into a viable stream of income is often a skill that photographers focus on less. For many photographers, this isn’t a problem as they prefer to keep photography as a hobby rather than a job.

However, I knew that I wanted to produce imagery for a living since I got my first camera, and being able to make a living through working with the subjects that I love has always been the aim.

With the intention of learning how to turn my hobby into a living, I went back to university in my late 20s to study Natural History Photography, and took advice from anywhere I could find it. Notably, I found great information from listening to photographer interviews/podcasts.

Additionally, if you’re looking to turn your photography into a business, I highly recommend attending networking events, such as Wildscreen, as they allow you to make connections that could help you find work later in life.

In this article I aim to share some key information I have picked up over the years, that will hopefully be useful for other aspiring outdoor image makers in a similar position.

Building clients

Initially, it is highly unlikely that clients will hire a photographer’s services without a strong portfolio behind them, with examples of work they have completed for other clients. Generally, I would always turn down a job for a client offering to ‘pay in exposure’, (oh yes, we’ve all heard that one before).

However, I have happily worked for free on my own terms. Sometimes I found interesting projects that didn’t have media funding, and would spend time producing some imagery that they could use for promo, etc. In turn, I knew I would be gaining skills and broadening my own portfolio.

Most regions have small conservation and wildlife organisations that would be happy if you could dedicate a little bit of time to helping. This work can provide great additions to your portfolio and will help the organisations too. It can also get your name in the mix if/when they are looking to commission future jobs.

Top tip

It is important to be very selective when finding organisations for which to produce free work. Large organisations factor in budgets for imagery and promotional material, and aspiring photographers giving valuable work away for free continually damages the value of photography, and makes it harder for anyone to make a living from the art.

This is why I always looked for small, local organisations, or projects which I knew could not afford to pay for photography, but had a subject matter that I found interesting. On multiple occasions this has led to the organisation seeking grant funding to pay for my work on future projects.

Types of jobs

I tend to break paid work down into two main categories: commissions and assignments.

1. Commissions

By my definition, a photography commission is a job in which a client wants images of a subject and provides a project brief and a deadline. It is the photographer’s job to take the brief and make it a reality.

This is often over a few months (or longer), so jobs like this can give photographers time to really delve into the subject, tell a story, and aim for some more difficult, and even experimental, shots over a longer period of time.

2. Assignments

Again, by my own definition, an assignment is when a client has an event or subject that they want to photograph, and you are despatched to cover it. Clients will generally give a shot list of subject matter that they want to be covered, and it is often shot over a week or so. Usually, the timing is based around the client’s planned events.

For example, I recently shot a tree planting event for a rewilding project in Yorkshire. For this I was sent up to the project for a few days, with a shot list to be delivered upon completion. As assignments are usually more time restricted, there is high pressure to ensure that as many images in a shot list as possible are created.

This often leaves the working photographer less time for experimentation. So, it is less likely that complex or hard to achieve shots (such as DSLR camera trapping) will be suitable.

Read more: How to Camera Trap Wildlife with a DSLR Camera

Top tip

Stick to what you know in these situations! They’ve hired you based on the skills you have demonstrated in your portfolio. You will likely have a limited amount of time and a shot list to cover, so make sure you have covered your bases with safety shots before trying something new.

Planning and understanding a client’s needs

Having a strong understanding of what a client is paying you to do is the difference between a happy client that will likely come back to you again and again with more work, and a client that writes you off.

If you can meet a client in person before a shoot, do it. However, these days most of my clients are based in a different location to me. So, I always try to get a zoom call (or two) in before the job, to really have a good grasp on their wants and needs from the shoot.

5 key details to establish

- Where is this media going to be used? This will inform the style, i.e., an international advertisement campaign will be shot in a very different style to newspaper or magazine press releases.

- What is the story, and what is your client trying to communicate with the photos that you are providing?

- Are there key landscape locations, flora, or fauna that the client wants to ensure are covered?

- What are the key points of the job? Will there be events unfolding and, if so, how much coverage does your client want of each of these events?

- Does your client have any dream shots and/or inspiration from photos or films that they have seen before, that they would like you to recreate?

From this information, you should be able to write up a shot list. I tend to create it as a checklist in my phone notepad, which I make sure is backed up on my iPad before the shoot. This means I will have a quick and easily accessible digital version that I can check off as I go.

I don’t tend to write up a contract for jobs (particularly if the client is reputable, or somebody that I have worked with on a number of occasions). However, I do ensure that I have a written paper trail of the agreed work, the signed-off shot list, expected delivery, and rates.

This is usually in the form of a formal quote for the proposed work. If the client responds by accepting the quote, you have a written agreement.

Recommended kit and photography techniques

Unless you are being commissioned to photograph a very specific shot or style, it is likely that you’ll be expected to be able to produce a range of images. These could potentially range from macro all the way to wide, drone-style landscapes, for coverage of a subject that will satisfy a client’s brief or shot list.

I recommend analysing the content that is put out by the clients that you would like to attract. You can work out what kinds of shots they like, and identify if there are any key styles or techniques lacking in their media.

This can give you a few core skills to focus on, ensuring that your work will resonate with them if you get the opportunity to pitch your services. Also, it can give you the opportunity to offer them something that they don’t already have.

As mentioned above, when working on assignments I always go through the client’s wants and needs, to create a strong and clear shot list. Before packing, I will walk through the shot list to decide what kit I will need to achieve it. There are few things worse than lugging unnecessary heavy bags/cases up a mountain, only to realise all you needed was a wide lens and a tripod.

My bag usually contains a pretty standard kit to have most of the bases covered. This includes a Sony A7IV for most of my stills work, and a Sony A7SIII. I like to carry two camera bodies, as I have had cameras from multiple brands fail on me in the field. To know that you have a backup in the bag adds a level of security.

Lens-wise, I recommend making sure that, at minimum, your bases are covered as best as possible. A standard zoom like a 24-70 mm can be useful for everything, from landscapes through to portraits and action shots. I like to carry a macro lens in my bag for closeups and details, which can really help bring a shot list together. I would recommend a 90 mm f/2.8 or similar.

A mid-range telephoto zoom like the 100-400 can be useful for species and detail shots. I also carry a few different tripods, a few speed lights (like the Canon 580EXii), and some universal wireless flash triggers, along with a Lastolite soft box.

As you build up clients you will be able to invest in a wider variety of lenses, but it is worth making sure that you can deliver the basics before investing in something more “exotic”. You might want to get every lens that you think you’ll need right off the bat, but I would always recommend ensuring that the lens, or any other bit of kit for that matter, is going to pay for itself.

For example, this summer I had several jobs shooting macro work, particularly wildflowers. I wanted to have something in my bag that would have me covered to shoot something completely different for each of my clients. I particularly wanted something that could show a flower up close without isolating it from its wider environment. So, I purchased the Laowa 15mm f/4 macro lens.

Read more: 10 Important Things to Keep in Your Camera Bag

Top tip

For people who are starting out, there are some great all rounder lenses that can help you have as many bases as possible covered. For example, the Canon 24-70 f/4 IS USM L lens is a cheap, relatively fast, light, and sharp standard zoom that has a specialised “macro” mode when at the 70 mm end of the focal range.

This won’t give you quite the same quality as a prime macro lens but, until you’re earning money from your photos, it can be hard to justify shelling out for multiple expensive lenses.

I also always carry a drone, although I should say that it is extremely important to be aware of the laws around flying drones, particularly for commercial clients. I have a CAA OA which means that I am authorised to fly for commercial operations.

Flying for a client without the proper credentials can land both you and the client in a lot of legal trouble, which of course would not keep you in their good books! Licencing can be expensive but, depending on who you’re hoping to attract as a client, it can be worth it to be able to offer that service.

Read more: Drone Laws: What You Can & Can’t Do

Mastering lighting

Many outdoor photographers (including myself) often want to avoid the use of flash. I always leaned on natural lighting, which is often completely acceptable.

However, when I began camera trapping, I soon realised that flash guns are necessary to freeze frames, particularly of fast-moving animals in low light. Because of this, I gained a quick understanding of how flash (when used well) can really make an image stand out.

Read more: How to Photograph Wildlife in Low Light

Often, clients will include on the shot list portraits of people involved in the project, performing their work. If the natural lighting is difficult or uninspiring, it can be hard to make these images work.

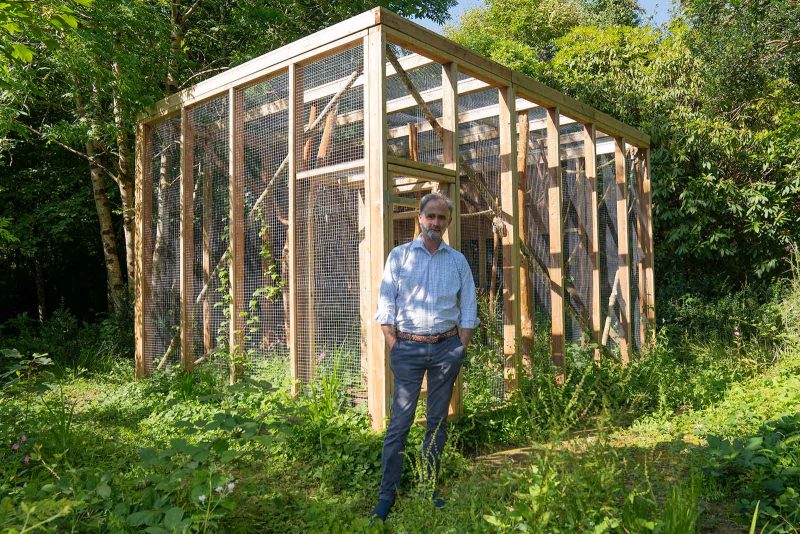

One of the first portraits I took was on commission for the Cornwall Red Squirrel Project. I had to take a portrait of the chair of the project in front of a captive breeding pen, but the sun was shining through the trees, creating light that was extremely hard to work with.

At the time, I didn’t want to appear to “waste” too much of the client’s time, which resulted in an image that I am not happy with (see above.)

For a portrait like the one above, I knew that I would be working in winter light early in the morning, so the sun would be low. In practice, the sun created a side light, meaning that the subject’s face was half lost to shadow.

So, I pre-set a Speedlight with a soft box on a small Manfrotto BeFree tripod to the left of frame, before asking the subject to stand in place. Often you can have the flash power set relatively low, but in this situation it meant that I was able to balance the exposure, and compensate for the shadows that were cast on the left side of the subject’s face.

Even now, as I don’t use flash day in day out, I tend to spend a few hours getting re-acquainted with flash and how to control light, ahead of going on a shoot on which I think I will need it. This can be with a family member, a friend, or even your cat!

A quick refresher can be extremely helpful in ensuring that your setup will be quick in the field. If you’ve fallen out of practice, you can find yourself in nightmarish situations like taking too much time when a client is clearly getting impatient or, worse, missing the shot.

Top tip

It is rare that you will get the exposure perfect on your first shot, so don’t be scared to ask your subject to stay put, and change the setting a few times. Even if you feel like you got it in the first shot, still just take a second for safety. The last thing you want is to get back to your hotel and notice that an eye was closed, for example.

For certain jobs I take a camera trap kit to deploy while I am shooting other images. When packing a camera trap kit, I have a standard setup containing a Canon 550D camera which I am comfortable leaving unattended, a Camtraptions PIR V3, 3 Nikon SB-28 Speedlights, and a selection of clamps, small tripods, etc.

I’ll spare more detailed breakdowns of my camera trapping techniques, as Nature TTL already has some great articles on this subject.

Read more: 8 Tips for Wildlife Camera Trap Photography

Editing your photographs

So far in my career, I have not had any clients request crazy edit styles. Basic editing and colour correction to make your photos look like smart, vibrant, and interesting takes on real life tends to be the style that most paying clients want to aim for.

This isn’t to say that, in challenging situations, an HDR isn’t valuable, but the overly saturated, avatar-looking HDR landscapes are rarely the ones that you’ll want to deliver to clients.

Natural, basic editing tends to be the best option. I use Adobe Camera RAW to do 90% of my editing. I tend to work to a concise workflow:

1. White balance

2. Fine-tune exposure (check highlights and shadows are all looking well-exposed)

3. Crop if necessary

4. Selective sharpening

5. Fine-tune saturation and luminance

6. If there are dust spots/ unwanted twigs or leaves, etc., I open Photoshop and remove these. It should be noted that this is acceptable for client work, as you want to deliver the smartest photographs possible. However, this is not acceptable if you plan to submit any of your photographs to competitions.

7. Save as both a JPEG and Tiff to provide your clients with a copy for web use and a copy that is print ready. It’s rare that a client will ask for this (as, let’s be honest, most of them won’t know the difference), but I find that if you explain the difference, they appreciate it.

Read more: Editing Your Photos: How Far Should You Go?

In conclusion

Taking the plunge to turn your hobby for outdoor photography into a career can be scary at first and, at times, can feel like you’re getting nowhere. But with perseverance, adaptation, and learning from your mistakes, you can make it happen.

I have had moments of feeling burned out or, to be honest, in a financially precarious place, but I kept going and in recent years have been able to make a reasonable living from my work.

The exciting thing is that, in outdoor photography, no two jobs are the same. Even if you’re working with a similar subject, there is always a challenge or new style to be found. Be sure to continue shooting your own passion projects in your own time. You’ll be surprised at how ‘that technique that you tried out for yourself’ can suddenly become relevant in the field.

There will be moments of frustration, as you may just want to spend all day photographing wild animals, landscapes, or whatever your preferred style. But, at the end of the day, being paid to take photographs outdoors is a real privilege, and something worth striving for.