Ross Hoddinott: From Amateur to Professional

In our interview series “From Amateur to Professional,” we will be asking established nature photographers to share how their photos and practices have developed, changed, and improved over time. You’ll get to see the progression of their images, learn how they got started, and find out how they transitioned from amateur to professional. To see more from this series, subscribe to our free newsletter.

Ross Hoddinott is one of the UK’s leading landscape and close-up photographers. He is the author of several photography books, including The Art of Landscape Photography, The Landscape Photography Workshop and From Dawn to Dusk: Mastering The Light in Landscape Photography.

Based in the south-west of England, Ross is best known for his intimate close-up images of nature and for evocative landscape photographs. He is an Ambassador for Manfrotto and, previously, Nikon UK (2013-15). He co-founded Dawn 2 Dusk Photography with photographer Mark Bauer.

When and why did you first catch the nature photography bug?

I caught the bug early. My parents were a massive influence. Neither were photographers, but they both had a passion for the natural world and conservation.

We moved to Cornwall when I was 7 years old and I was surrounded by coast and countryside. They bought an old farmhouse and a few acres of land, which we transformed into a young woodland by planting several hundred trees. We also created two ponds and planted wildflowers. It was fascinating to witness how quickly nature adapted to the change of habitat.

My mum would teach me the names of trees, flowers and insects. I had amazing freedom and would spend hours looking for birds and bugs. I think I was 10 years old when mum and dad bought me a little compact film camera for Christmas. I hadn’t asked for a camera, but quickly fell in love with taking photos and, due to my passion for nature, I instinctively wanted to photography wildlife.

My firsts efforts were pretty terrible. I’d try to photograph things like buzzards soaring above, but they just appeared as a tiny dot. My parents had an old Zenit 11 SLR camera gathering dust that they let me use. It was a brick of a camera – very basic – but at least I could change lens and attach filters.

A friend of the family was a keen photographer and kindly gave me a close-up filter. This enabled me to capture frame-filling shots of flowers and insects. And that is when my photography really began to gain momentum.

Show us one of the first images you ever took. What did you think of it at the time compared to now?

All my early efforts were shot on 35mm negative film – made by Boots or Bonusprint (if you remember them!). Not many of my early prints have survived, which is probably a good thing to be honest!

However, one of my very early efforts actually proved to be the catalyst for my career. A year or so later, aged 11, I took a photograph of paired emperor dragonflies by one of our ponds. I just happened to be out with my camera when I spotted them land. I creeped up close and, using the Zenit with 50mm lens and +3 close-up dioptre, I took a series of shots.

The camera was completely manual and I’m not sure how much I really understood about exposure and technique at the time. However, the shots weren’t too bad and my dad suggested I entered them into a new photography competition run by BBC Countryfile.

I did exactly that and, to my absolute amazement, I won the under 18 flora and fauna category. It was an amazing confidence boost. Dad took me up to BBC Pebble Mill for the show and John Craven interviewed the 9 winning photographers (adult, junior and professional winners in three different categories) live on TV before a phone vote to decide the overall winner. I missed out on the Safari to Kenya, but won a top of the range Minolta SLR camera.

At such a young age, this really sparked my interest. It is not a great shot – particularly by today’s standards. I wouldn’t even take the photo now – I’d look at the messy background and disregard the opportunity. However, at the time, for a kid with such a basic set-up, I guess it was a decent effort. And had I not taken that shot, I might now be doing something very different… who knows?

Show us 2 of your favourite photos – one from your early/amateur days, and one from your professional career. Tell us why they are your favourites and what made you so proud of them at the time. How do you feel about the older image now more time has passed?

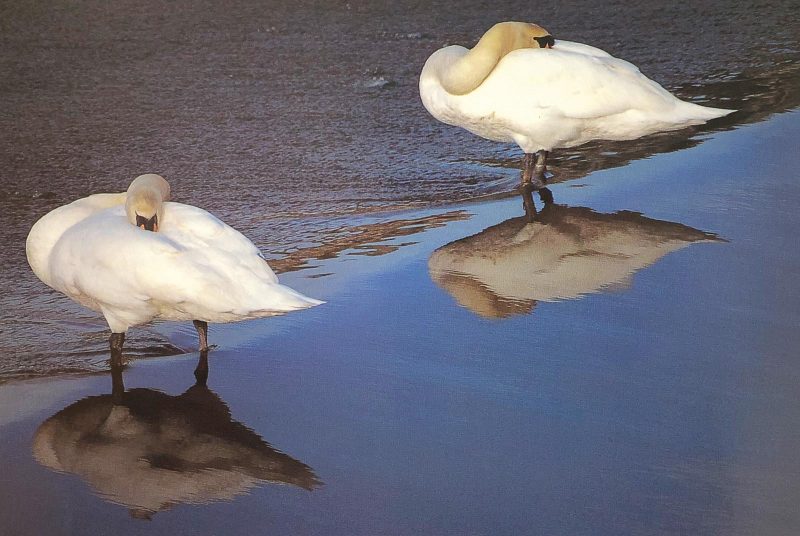

The first image here I took aged 16, using the Minolta Dynax camera I won in Countryfile’s photography competition. I wouldn’t necessarily describe it as a favourite, and it doesn’t stand up well against wildlife images today. However, this photo won me Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year in 1995 – a significant stepping-stone in my career. As such, I look back on the image fondly and am grateful my amazing dad agreed to drive me to a local reservoir on that particular day, and that I spotted these resting swans and the picture potential of their symmetry.

The second image is a photograph I took of a robin in my back garden during a whiteout some years ago. We were snowed in at home, so I spent my time photographing the birds in our backyard visiting the feeders. It’s certainly not a planned shot. I just happened to be focused on this particular bird when another robin got too close and it reacted aggressively – puffing out its feathers and flicking up its tail. I took one frame and it just happened to be pin sharp and perfectly timed.

It is an exceptionally lucky shot – but I guess I made my own luck by lying out in the snow for hours on end, freezing my whatsits off! I’m not a bird photographer, yet it is probably my most successful image – selling to Tesco and countless publications – and it was also selected for 50 Years of Wildlife Photographer of the Year – a book celebrating the best 100 images of the competition. An amazing accolade that I am very proud of.

Both images, while not my best, have been landmark photographs in my career and I remain fond of them to this day.

When did you decide you wanted to become a professional photographer?

I think I made that decision somewhere in my mid-teens. By this point I was actually selling photographs fairly regularly – with my shots being used in local magazines, for postcards and in the photo press. I wasn’t making much money, but enough to save up and buy a new piece of camera kit every now and then.

Aged 16 or 17, I got my first contract with a photo library. This would have been in the mid-90s when stock was still relatively lucrative – before the days of online libraries, royalty free images, and micro fees.

You had to earn a contract with an agency and then had to supply a minimum number of images per year of the required standard. Making my first stocks sales was really exciting – incredibly, one of my very first sales was for £5000! I understandably assumed that I would just earn more and more from stock as I took and submitted more and more photos.

Learn more: Breaking Into Business

Unknowingly, I was already laying the foundations of my career during my teens – establishing my name, connecting with magazines, and building a portfolio. The decision to go pro was never really a very conscious one, just a natural progression I think.

How did you transition into this and how long did it take?

From the age of 18 until my early twenties, I worked part-time behind a bar in a local pub and also coached archery to give myself regular, guaranteed income. The rest of my time was dedicated to either taking photos, submitting images to publications, or writing.

I quickly realised that the ability to take a decent photo didn’t mean anything unless I was prepared to really graft. Transforming the odd sale into a full-time living took me longer than I thought. I had some dark days when one rejection slip after another really got me doubting myself and my ability. I had no plan B – photography was the only thing I had ever wanted to do.

Other than GCSEs, I had no other qualifications or skills; I had firmly put all my eggs in one basket. My parents were always supportive, though – their belief in me never wavered. By this time I had also met Fliss (now my wife, and mother of our three amazing children), who was equally encouraging. It makes a big difference in life when you have the right people around you.

Aged 21 or 22, I was just about making enough money from photography to quit the part-time jobs. Money was tight and I struggled for a couple of years until I could honestly say I was making a living from taking photos. It was a tough transition, but I learned valuable life lessons.

Was there a major turning point in your photography career – a eureka moment of sorts?

Yes, there was actually. One was winning Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year in 1995. That was a big deal – lots of publicity and a great confidence boost. I made some good contacts and winning such a big contest put my name in front of lots of the right people.

In fact, looking back, doing well in photo competitions has really helped accelerate my progress. However, the main ‘eureka’ moment was switching to digital.

I guess I was in my mid-twenties when digital SLRs were finally good enough to be a genuine alternative to film. I’m a longstanding Nikon user and the 6-megapixel D70 was their first affordable DSLR.

At the time I was shooting transparency film – mostly Fuji Sensia or Velvia. Film wasn’t cheap to buy, or process, and slides needed to be mounted. You couldn’t vary ISO or review exposure or results after releasing the shutter. The cost of film was prohibitive – I had to watch the pennies, so had to think about every frame I took.

I couldn’t take risks or be creative for risk of waste. And then sending originals away to publications was always risky – what if your valuable shots got lost in the post, or damaged? I sent all submissions via recorded delivery and enclosed return postage. It was a slow, costly process to send images to anyone. Digital revolutionised the way I worked.

The Nikon D70 represented a big investment for me, but within weeks I had sold my film camera and never shot film again. I loved the freedom digital gave me. I could be experimental and innovative without it costing a penny – I could see my mistakes as I went along and quickly learn and progress.

Being an early convert to digital also gave me an advantage in the marketplace – photo mags needed digital images and photographers to write about digital photography while the industry switched from analogue. I could quickly send files via email, rather than use snail mail.

The whole process liberated me, and I quickly went from being a struggling pro to one who was earning a proper living. To be honest, I think switching to digital saved my career.

Are there any species, places or subjects that you have revisited over time? Could you compare images from your first and last shoot of this? Explain what’s changed in your approach and technique.

As a landscape photographer, there are countless locations I’ve visited repeatedly – and as a nature photographer, there are many species I’ve worked with time and again. It is imperative you do this. To get the very best from any location or animal, you need to have an intimate knowledge of your subject.

For landscapes, you need to know tides, the position of the sun and its influence at different times of the day, seasonal changes and how weather can impact the scene.

For wildlife, you need to understand a subject’s lifecycle, behaviour, preferred habitats, routines and diet in order to achieve the best results. Working consistently with a species is normally the best route to achieve those truly ‘special’ or unique shots. Investing time, doing your homework and creating opportunities for yourself is essential.

To give you an example, I’ve been photographing large red damselflies since I first picked up a camera. They are a widespread species, but I enjoy working with animals on my doorstep – there is something hugely fulfilling about taking a great image of a common, everyday subject. I prefer to do this than travel to some far-flung place to take a shot everyone else has done before.

Each spring I discover something new by spending time photographing the same species. The more extensive your knowledge, the better your shots will normally become. Once you have captured the more obvious angles and portraits, you have to work harder to produce something better or different of the same subject.

For example, my first shots of large red damselflies were nice enough studies, showing the subject in close-up and sharp throughout.

Now, my aim is very different. ‘Nice shots’ just won’t cut the mustard any longer. I want to capture behaviour, context or do something creative instead. For example, I might capture the subject smaller in the frame and show it within its environment, or crop in tightly to highlight shape, form or colour.

By working with a subject year after year, your aim and emphasis changes as a photographer – and this is when you are most likely to capture something special. You can be more selective in your search for something fresh.

While I don’t dislike the ‘conventional’ shots I took years ago, I much prefer the more arty and creative interpretations I aim to capture now. Our styles, skills and vision as photographers must always evolve.

What’s the one piece of advice that you would give yourself if you could go back in time?

That’s a tricky one to answer. I’ve made my share of mistakes, but they’ve all shaped who I am and helped me to get where I am today, so I don’t really have any major regrets. I’m not really a risk taker, and I’ve definitely let a few opportunities slip through the net as a result of being too practical. But I think the advice I would actually give a younger me would be to simply spend more time behind a camera being creative.

So much of my working life now is spent in front of my iMac either writing features, replying to messages, organising workshops or editing photos that I just don’t have the freedom I would like to take the photos I want. I know I sometimes get my priorities wrong, always wanting to hit every deadline rather than asking for an extension in order to get out and make the most of the here and now. Or postponing a shoot in order to clear a full inbox – I hate getting behind with work.

However, in hindsight, photography should always come first.

What was the biggest challenge you faced starting out, and what’s your biggest challenge now?

When I started out, good photographs had a value. The fees associated with being published were ok and – as I touched upon earlier – stock had the potential to be provide regular sales and a decent income. But it was so hard to get your name seen and established. The internet was relatively new and social media didn’t exist, so getting your images in front of the right people was a genuine challenge. Or at least I found it so as a young, fresh-faced wannabee.

Today, the opposite is true in many ways. It is easy to share images and get your photos seen through a personal website and regular social media posts or even create your own YouTube channel. But while it is obviously very nice to have thousands of likes and followers, how do you convert this into a living?

While good photos were once a premium, now there is a wealth of extraordinary images by a wealth of extraordinary photographers. Supply now massively outweighs demand, which is why most images are now valueless. We are exposed to so many wonderful images that we are steadily growing immune to their quality, impact and creativity.

Young photographers today face a very different set of challenges to when I started, and suffocating levels of competition. As a result, the profession faces an uncertain future, I fear.

You can visit Hoddinott’s website to see more of his work. For more from this series, subscribe to our free Nature TTL newsletter.